Climate change is a global issue, but its impacts vary greatly by location. Where a person lives plays a significant role in their ability to manage rising temperatures, worsening air quality, and increasingly frequent natural disasters. As a result, place-based efforts play an important role in improving communities’ sustainability and resilience to climate change. Like many cities across the U.S., Oakland has a long history with environmental justice, the idea that environmental benefits and burdens should be shared fairly among all people. Over the years, the City has taken steps to become more sustainable, seeking to adopt a holistic approach to achieve climate equity.

Environmental impacts are not distributed equally in the status quo, partly as a result of past urban planning strategies. Policies such as redlining – a practice where banks and other institutions refused financial services to customers based on race or ethnicity – prevented investment in communities with more people of color, concentrating lower-income people of color in less favorable neighborhoods. These areas were often targeted as sites for industrial and freeway development as they were perceived as ‘less desirable’ and residents lacked the political power to stop the projects. The Federal Government banned redlining in 1968, but its effects are still felt today. Residents of formerly redlined communities – including those in Oakland – often face increased levels of air pollution, exposure to toxic substances, and extreme heat compared to other neighborhoods. Climate change will continue to magnify these disparities, exacerbating redlining’s impacts.

Image Source: Greenlining Institute

Environmental Activism in West Oakland

Community groups have driven progress on environmental and public health issues in Oakland. In West Oakland, a majority Black community, community activists and organizations have been fighting for decades to improve their neighborhoods’ environmental quality.

West Oakland borders the Port of Oakland, three freeways, and the Oakland Army Base (although it was decommissioned in 1999), resulting in elevated freight and truck activity. As the Port of Oakland grew, becoming the largest in the Bay Area in the 1950s, higher numbers of diesel trucks drove through West Oakland carrying cargo to and from the harbor. The trucks’ emissions increased West Oakland’s levels of airborne, toxic diesel particles to some of the highest in the Bay Area, raising residents’ risk for health problems such as asthma and cardiovascular issues.

As Oakland’s port became one of the ten busiest in America, community members took action to address the worsening environmental and health impacts. Following the 1989 Loma-Prieta earthquake and the subsequent collapse of the Cypress Freeway, West Oakland residents successfully lobbied the city to rebuild the freeway further west, so that it no longer bisected the community. The victory created a buffer between the pollution from the heavily-used highway and community members while also rejoining smaller, local roads to reconnect neighborhoods divided by the freeway.

The momentum continued into the 1990s as Margaret Gordon, a local activist and third-generation West Oakland resident, led a series of campaigns to clean up the area. Gordon noticed how soot often collected on her windowsills and that many of her West Oakland friends and family had asthma. Thinking the diesel trucks constantly driving through her community could be responsible, Gordon co-founded the West Oakland Environmental Indicator Project (WOEIP) in 2002 to investigate. WOEIP brings science and community voices together to create positive environmental change. This multidisciplinary approach resulted in a formal recognition by the EPA in 2006 for the organization’s environmental research and efforts to improve local air quality.

Gordon and WOEIP have seen some progress as the Port has taken steps to approve an air quality improvement plan, began implementing a Truck Management Plan in 2019 to reduce their trucks’ impact in West Oakland, and started an electric truck pilot program. In 2018, the Port of Oakland’s diesel particulate emissions dropped 81% from 2005 levels, demonstrating the power of community action to create environmental change. Groups like WOEIP will continue to play a role in improving environmental conditions in Oakland. As recently as 2017, WOEIP filed a civil rights complaint against the City of Oakland due to its continued expansion of freight activities at the Port of Oakland and Oakland Army Base without proper health protections.

Oakland’s Environmental Action

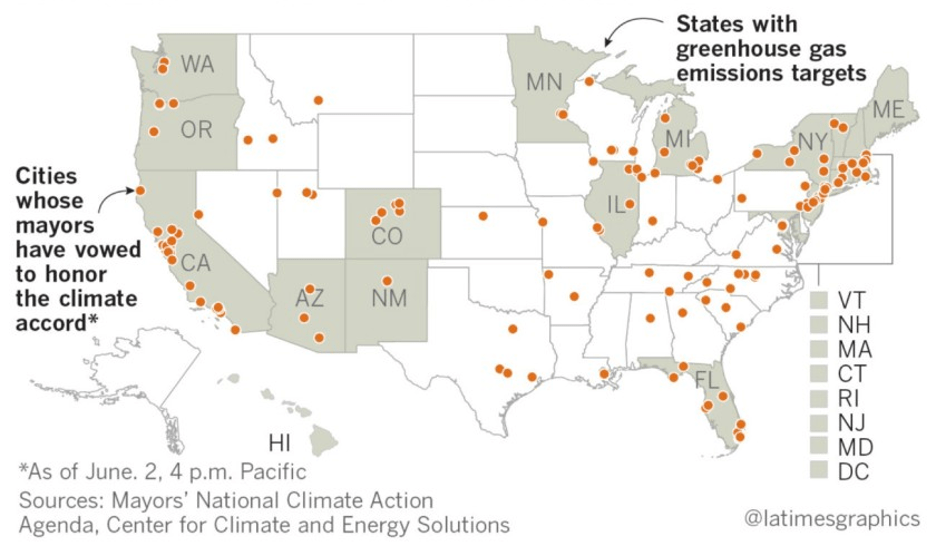

Motivated by community action and the worsening effects of climate change, the City of Oakland has recently adopted numerous measures to reduce public health and environmental disparities. One of Oakland’s strategies has been to join environmental covenants like the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change. Signed by 197 nations, the Agreement aims to mitigate the negative impacts of climate change and global temperature rise; Oakland has committed to limiting local greenhouse gas emissions to 80 to 95 percent below 1990 levels by 2050 in an attempt to keep global warming below 2°C by the end of the century. Though lacking in concrete actions or enforcement, covenants provide environmental goals and benchmarks to orient the City’s decisions. City resolutions serve a similar function. In 2018, the Oakland City Council passed a Climate Emergency and Just Transition Resolution, calling for urgent action to address climate change, increase resilience, and better support frontline communities.

Credit: LA Times

Oakland has created a series of plans to more directly guide city actions to achieve the sustainability and resilience goals set out in the City’s covenants and resolutions. A main goal in these plans is to prioritize and protect communities that are most impacted by climate change. In 2020, Oakland adopted the 2030 Equitable Climate Action Plan (ECAP) which provides a framework for equitably addressing climate change in Oakland. Over 2,100 residents and a range of technical experts contributed to the plan. Key goals include encouraging the growth of Oakland’s green economy, addressing structural vulnerabilities in frontline communities, and lowering greenhouse gas emissions. As a companion to the ECAP, the City’s Equity Facilitator team created the Racial Equity Impact Assessment and Implementation Guide (REIA) which includes guidance on how to implement Oakland’s sustainability goals while supporting racial equity and strengthening community oversight. These plans set the groundwork for Oakland to become a more sustainable and equitable city. Nevertheless, it is important that funding is allocated for programs, initiatives, and projects which carry out ECAP and REIA guidelines in order to have a tangible impact.

Looking to the Future

Implementation of Oakland’s environmental plans is critical to addressing the growing impacts of climate change. Scientists predict that by the end of the century, Bay Area temperatures may warm by as much as eight degrees Fahrenheit and sea levels may rise by three feet. In addition to Oakland’s plans, community organizations have produced creative strategies to mitigate climate change’s effects and foster vibrant, healthy areas. The replacement of the I-980 freeway is one such plan. I-980 cuts through West Oakland and has been criticized for isolating the neighborhood and leading to decades of decline. In 2017, the Congress for New Urbanism named the highway one of the ten most obsolete freeways, lending steam to the movement to replace it. ConnectOakland, a group with goals of improving transportation in Oakland, proposed turning the highway into a tree-lined boulevard surrounded by parks, housing, and neighborhood retail. The plan aims to reconnect and revitalize the area while supporting walking, biking, and transit to reduce vehicle emissions. A collection of local leaders, including Mayor Libby Shaff, and activists have supported the plan which could receive a further boost from President Biden’s infrastructure plan which calls for highway removal to right historical injustices. Innovative environmental efforts could play a role in mitigating climate change, yet it is essential these measures center those most vulnerable to climate change’s impacts to create a more equitable, sustainable, and healthier Oakland.

Cover image: Trucks Leaving the Port of Oakland. Credit: KQED